What is Endometriosis?

Endometriosis is the abnormal growth of endometrial like tissue outside the uterine cavity that can cause chronic abdominal pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia and infertility. Although the disease is common and nonmalignant in nature, the symptoms can severely impact function and quality of life. Treatment options for endometriosis are limited and not well understood despite a growing need.

What are the effects of endometriosis on lifestyle?

Symptoms are known to be painful and debilitating to patient function, affecting:

- sleep

- employment

- sexual function

- mood

Women with endometriosis related to painful intercourse have lower sexual function, which decreases their quality of life and causes relationship distress with their partners.

Endometriosis affects approximately 5% of women of reproductive age, particularly between 25 and 35 years of age.

The estimated total annual cost of surgically confirmed endometriosis is $1.8 million. Chronic pelvic pain (CPP) resulting from endometriosis is multifactorial, with neuropathic, myofascial, and central pain components.

How can endometriosis cause pain within the body?

Endometriosis resulting in neuropathic pain may occur due to invasion of endometriosis into pelvic nerves or spontaneous pain resulting from compression of pelvic nerves including the muscles covering the outer part of the pelvis, pudendal, ilioinguinal, iliohypogastric, genitofemoral, or lateral femoral cutaneous nerve.

The sensory fibers innervating endometrial lesions include C-fiber nociceptors, which are responsible for the burning pain sensation from noxious heat stimuli.

Peripheral sensitization occurs as a result of the lowered activation threshold of the nociceptor (sensory receptors for painful stimuli) due to their prolonged or recurrent activation. Nociceptors can facilitate sensitization by secreting neuropeptides, which initiate neurogenic inflammation, increasing receptor expression along peripheral terminals, and activating previously inactive visceral nociceptors with intense stimulation.

Continuous nociceptor activation sends afferent signals to the spinal cord, which cause structural and functional changes, ultimately leading to central sensitization and an exaggerated response to peripheral stimuli. Clinically, central sensitization results in allodynia, hyperalgesia, and referred pain.

How are endometriosis and chronic pelvic pain related?

Often, patients with chronic pelvic pain seek treatment from various health care providers without finding a definitive diagnosis or treatment plan. Recognizing central sensitization in chronic pelvic pain can help the physician and the patient to understand the physiology behind their symptoms and offer management strategies to defeat the cycle.

Myofascial dysfunction, which is a chronic pain disorder that causes pressure on sensitive joints, also known as trigger points, contributes to chronic pelvic pain and has been associated with endometriosis.

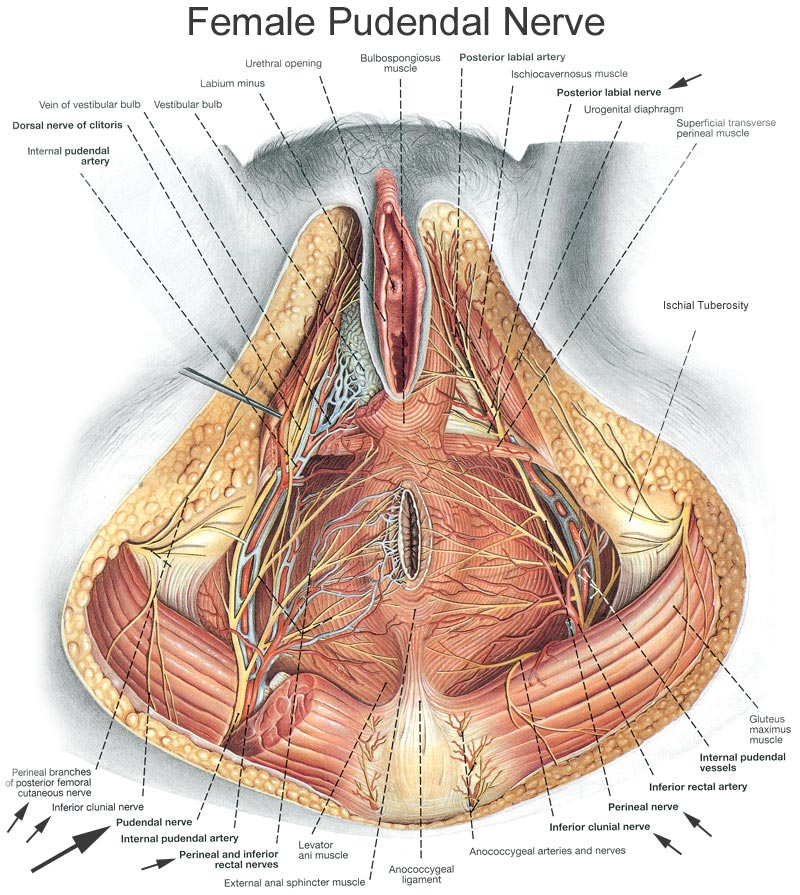

The muscles of the pelvic floor are arranged in two main layers: the superficial layer and the deep layer. The superficial layer, which is part of the urogenital diaphragm, is composed of the bulbospongiosus, ischiocavernosus, and superficial and deep transverse perineal muscles. The deep layer forms the pelvic diaphragm and is known as the levator ani muscle group, consisting of the puborectalis, pubococcygeus, and the iliococcygeus. These muscles and their associated innervations can be seen in Figure 1. Other deep muscles include the external rotators of the hip: piriformis, quadratus femoris, superior and inferior gamelli, and the obturator internus.

With chronic pelvic pain, there is cross-sensitization among the structures of the pelvis including the uterus, bladder, and colon, and their surrounding supporting structures, as well as the pelvic floor musculature itself. Cross-sensitization in these pelvic structures means noxious stimuli from the affected structure is transmitted to an adjacent normal structure, causing functional changes in the latter. This occurs via convergent neural pathways of the noxious stimulus transmission from two or more organs.

In other words, sensory information from individual structures converge at shared sensory neural pathways throughout the central nervous system (CNS), including at the dorsal root ganglion, the spinal cord, and the brain. This viscerosomatic convergence explains how the ongoing noxious visceral input can sensitize multiple areas of the spinal cord, generating the broad areas of allodynia, hyperalgesia, and referred pain seen with somatic dysfunction.

How can pain from endometriosis be treated and managed?

Treatment options for endometriosis-related symptoms are not well understood despite a rising need. Traditionally, treatments for endometriosis have focused on hormonal therapies and excision surgery, both of which target ectopic endometrial lesions. These approaches are essential in excising and decreasing the extent and recurrence of the pro-inflammatory endometriosis lesions.

However, pain often persists following hormonal treatments and excision surgeries due to myofascial pain, neurogenic inflammation and central sensitization. Other treatment modalities for chronic pelvic pain related to endometriosis include:

- neural blockade

- decompressive and surgical interventions

- medical management

- physical therapy

- alternative modalities

Nerve blocks are both diagnostic and therapeutic. Practitioners may use diagnostic nerve blocks to easily accessible peripheral nerves such as ilioinguinal or lateral femoral cutaneous nerves to confirm diagnosis.

Nerve blocks are used to reduce spontaneous ectopic activity of the nerve involved in many peripheral neuropathic pain disorders. Although many women may self-medicate with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications over the counter, evidence on their efficacy is lacking. For neuropathic pain, topical local anesthetics and topical capsaicin may be effective in treating localized pain and can be used as an adjunctive treatment, but they do not encompass the complete process involved in endometriosis-associated pelvic pain.

Trigger point injections with local anesthetics, such as lidocaine or bupivacaine, with or without corticosteroids, have been utilized to treat myofascial pain conditions associated with chronic pelvic pain. Peripheral nerve hydro dissection involves using an anesthetic or solution to separate the nerve from surrounding tissue, fascia, and adjacent structures, allowing the nerves to reset and decrease hypersensitivity.

What do nerve block injections do to help with pain relating to endometriosis?

In women with a history of endometriosis, the location of the ectopic lesions does not necessarily correspond with the areas that women identify as most painful. Given that the aim of traditional treatment, such as surgical resection and hormonal therapy, is to target these lesions, additional modalities are needed for pain control. Myofascial dysfunction and associated trigger points contribute to chronic pelvic pain and have been associated with endometriosis. A trigger point injection is thought to cause a mechanical interruption to the hypercontracted fibers via the needle itself and a blockade of pain signals via the substance injected.

In addition to nociceptive pain, myofascial trigger points can contribute to centralized pain, or the sensitization of the central nervous system that is seen in endometriosis. Centralized pain can be thought of as a maladaptive central nervous system response to continuous pain signals from the pelvis. With these abnormalities in pain signal transmission, symptoms may be out of proportion to the stimulus and not correlate with the expected dermatomal patterns. This central amplification in pain processing is thought to be responsible for accompanying somatic symptoms such as fatigue and sleep disturbance.

Furthermore, as mentioned previously, pelvic nerves can be irritated by endometrial lesions or become entrapped by postoperative scar tissue, further contributing to central sensitization and subsequent pain. Although the literature is sparse, there are case studies demonstrating ilioinguinal, iliohy ogastric, and pudendal nerve entrapments after abdominal and cystocele surgeries, with pain symptoms becoming less intense after suture removal.

In addition, given its location within the pelvis, the pudendal nerve may be compressed between the sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments or along any of its branches by pelvic floor muscle spasm from chronic guarding. Given the possibility of nerve invasion and/or entrapment in women with endometriosis, decompressive interventions may be effective. Although not surgical decompression, hydro dissection is a much less invasive modality with a similar goal of creating space for the pudendal nerve.

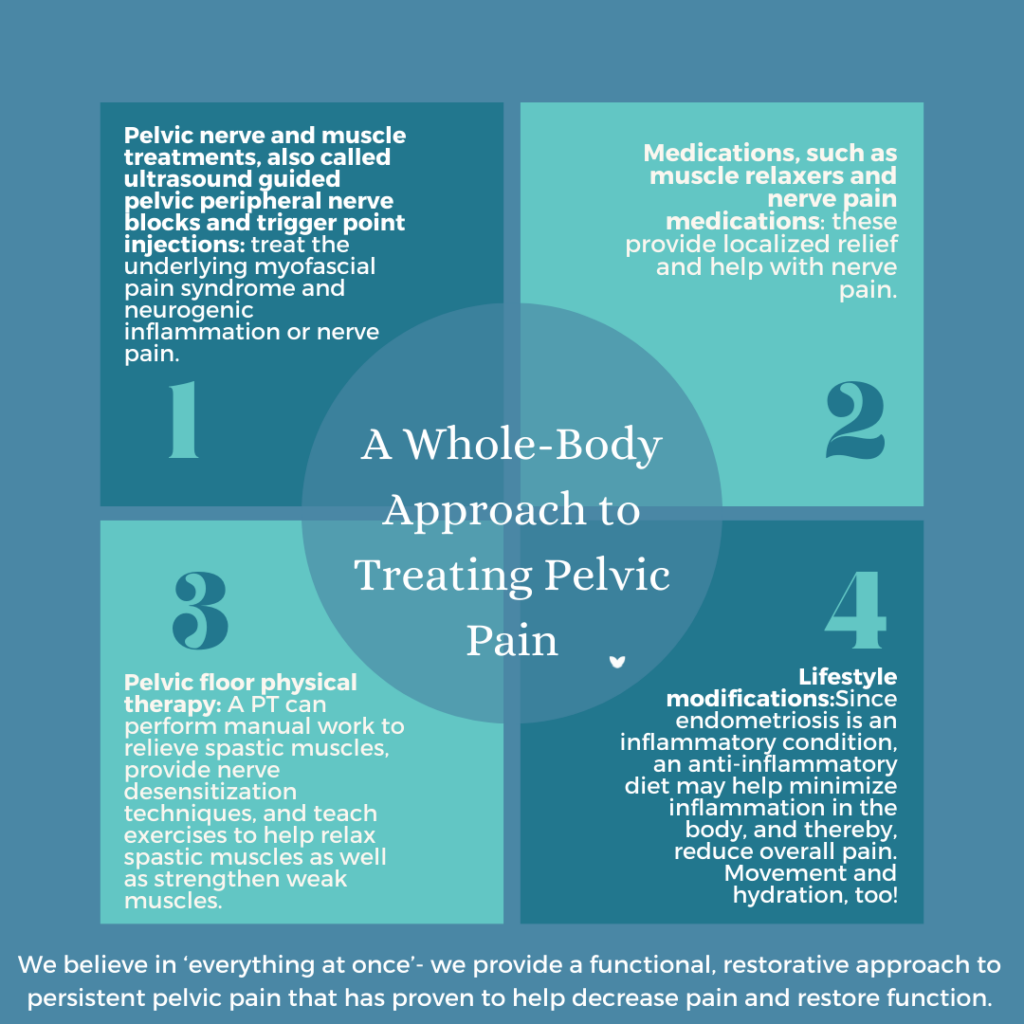

Finally, physical therapy, being a manual technique with minimal risk, may be beneficial with myofascial dysfunction and connective tissue release, dampening ectopic nerve activity. We propose that if pain persists after resection of endometriosis and optimization of hormonal management of the disease, it is important to think of treating the myofascial pain, neurogenic inflammation, and central sensitization associated with chronic pelvic pain.

What is PRM’s approach to treating and managing pain relating to endometriosis?

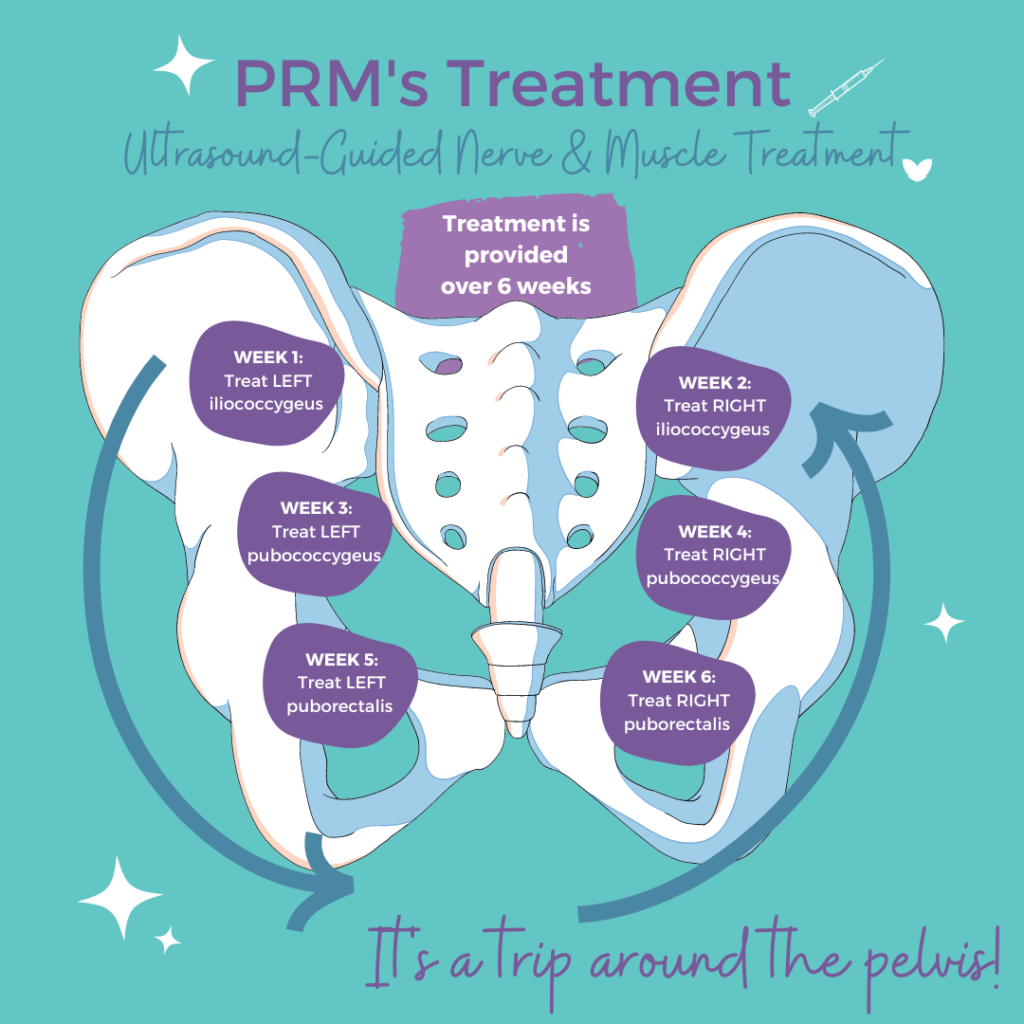

PRM uses an approach to treatment that includes treating myofascial pain, neurogenic inflammation, and central sensitization, essentially breaking the pain cycle. Our treatment protocol consisting of a combination of trigger-point injections, peripheral nerve hydro dissection and pelvic-floor physical therapy is a multimodal approach aimed at the multiple facets that contribute to pelvic pain.

It happens in three parts:

- Create space and increase blood around peripheral pelvic nerves via a peripheral nerve hydro dissection technique in combination with post-treatment nerve gliding with physical therapy. This increase in blood flow normalizes the local pH of the pelvic floor environment, which ultimately acts as negative feedback for the stimulation of the inflammatory cascade.

- Desensitize hyperactive peripheral nociceptors and stop aberrant firing of these nerves. Repetitive use of an Na channel blocker will desensitize and ultimately reset aberrant peripheral nerves. In addition, lidocaine itself has some anti-inflammatory properties.

- Utilize trigger-point injections and reset a short, contracted, weak muscle spindle. In addition, several studies have demonstrated decreasing the aberrant firing of peripheral nerves, which will then decrease the abnormal signaling to the spinal cord and brain, and ultimately decrease central sensitization.

Would You Like to See a Specialist?

Call us at (646) 481-4998 or click to request a regular appointment.